The Quiet Before the Dawn

June 3, 2010.

New York City slept beneath a humid summer sky. Outside the window of a small Upper East Side apartment, the streetlights hummed in soft orange, casting their tired glow across the blinds.

Inside, Rue McClanahan lay surrounded by the quiet rhythm of a hospital monitor and the low murmur of nurses who had learned to walk without sound. She was 76 — fragile, beautiful still, her hair a soft halo of silver, her breath faint but steady.

Those who were there that night say there was no drama, no struggle, no fear. Only peace — the kind that feels like forgiveness.

At exactly 1:00 a.m., the light in her room flickered once — a tiny pulse — and dimmed, as if the world itself was taking a slow, deep breath.

And then, everything stopped.

They say time hesitated in that room — that even the machines didn’t beep for a full second. It was not the end of Blanche Devereaux, the woman of laughter and lipstick and mischief. It was Rue — finally letting go, after a lifetime of pretending she never would.

The Woman Behind the Laughter

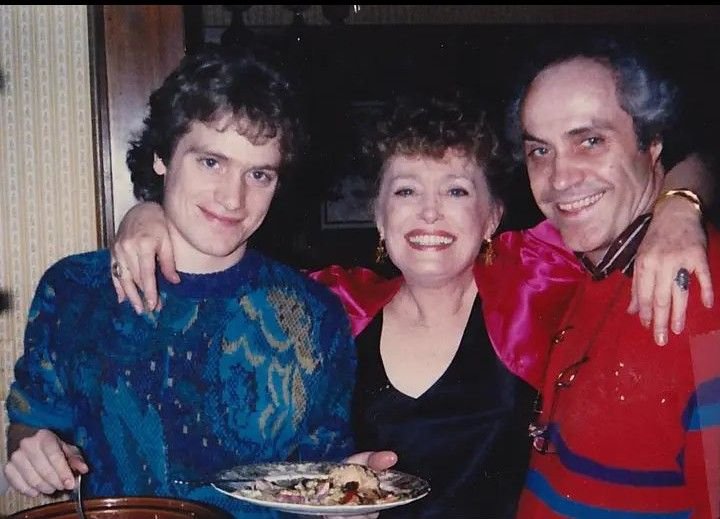

For millions, Rue McClanahan was Blanche — bold, witty, unashamedly alive. Her Southern drawl could slice through a room like sunlight through lace curtains. But behind the sparkle was a woman who knew loneliness too intimately to ever mock it.

Born in Healdton, Oklahoma, Rue came from dust and resilience — a preacher’s daughter who grew up believing that good girls didn’t dream too loud. But she dreamed anyway. Broadway first, then television, then immortality through The Golden Girls.

She used to joke that Blanche was “what would’ve happened if Rue had more nerve and fewer rules.” But the truth, as her closest friends knew, was softer: Blanche was Rue’s armor. The glamour, the jokes, the flirtation — all of it was a shield for the small-town girl who had been told she was never quite enough.

Betty White once said, “Rue had a heart that could fill a room — but she hid it behind humor, the way you hide a scar with jewelry.”

That night in 2010, as her body gave way to the slow rhythm of goodbye, the world was remembering a star. But those at her bedside were remembering a woman.

The Days Before

The final week had been quiet.

After her stroke earlier that year, Rue’s health had declined rapidly. She had stopped doing interviews, stopped answering calls. But she kept a journal — her last one — a small notebook with a golden cover, where she scribbled half-formed sentences and memories that felt too heavy to say aloud.

On one of the final pages, she wrote:

“I hope I see Bea again. She’ll probably roll her eyes and say, ‘You’re late, Blanche.’ And I’ll say, ‘I was picking out a dress.’”

She also mentioned Estelle Getty — “Sweet, tiny Estelle” — and how the world didn’t understand what courage it took for Estelle to act when her memory began to fade. Rue ended that entry with a sentence that still feels like a farewell letter:

“We were four women on a couch, pretending to be friends. And then we weren’t pretending anymore.”

Her son, Mark Bish, visited her every day. He brought flowers — always lilies — and sat by her bed reading lines from old scripts. Rue couldn’t always respond, but sometimes she smiled, and once, when he read the line “Nobody ever believes me when I’m sincere,” she managed to whisper,

“Still true.”

The Final Night

June 2 had been a long day. Nurses said she was calm, quieter than usual. She had asked to hear Ella Fitzgerald’s “Someone to Watch Over Me.” The song played softly from an old CD player beside her bed.

A friend, actress Elaine Stritch, had stopped by earlier in the evening. She kissed Rue’s forehead and said, “You did it, honey. You made ‘em laugh, you made ‘em cry, and you made ‘em remember you.” Rue’s lips curved in a faint smile.

By midnight, the hallway outside her room was silent. Her son, exhausted, had fallen asleep in the chair by the window. A single lamp was on — its light catching the framed photo of The Golden Girls that sat beside her water glass.

In the picture, Rue was laughing — eyes half-closed, Bea beside her smirking, Betty grinning wide, and Estelle caught mid-joke. It was joy immortalized in one frame — and somehow, that joy felt alive in the room.

Around 12:45 a.m., Rue stirred. Her breathing grew shallow. Her hand moved slightly, as though reaching for something.

The nurse, standing quietly nearby, stepped closer. Rue’s lips moved. She said something faint — a whisper too soft to record. The nurse leaned in, and later, when asked, she could only recall fragments:

“Tell them… we’re all right… all together…”

At 1:00 a.m., her pulse slowed, then faded. The nurse looked at the clock. And in that exact moment, the lamp flickered — once, twice — and dimmed.

The Witness

The nurse who had been in the room that night never spoke publicly again. Not to the press, not even in interviews about celebrity deaths. But years later, her daughter — herself a nurse — revealed what her mother had once told her, in a trembling voice.

“She said the strangest thing happened when Rue passed,” the daughter said. “For a second, she thought she saw movement in the reflection of the window — like four women standing side by side, smiling. And then it was gone.”

The nurse never claimed it was real. She wasn’t spiritual, not the type to see ghosts. But she said it didn’t feel frightening. It felt familiar.

“Maybe it was the reflection of the photo,” she said once, years before her own death. “Or maybe it was them. Who knows?”

What Came After

News of Rue McClanahan’s death spread quickly the next morning. Fans flooded social media with tributes, clips, and quotes from The Golden Girls. Lines like “I’m not one to blow my own vertubenflugen” or “Better late than pregnant!” were everywhere — reminders of the laughter she left behind.

Betty White, the last surviving Golden Girl, was filming Hot in Cleveland at the time. When reporters asked her for comment, she paused, tears in her eyes, and said,

“Rue was a spark — she could light up a room and then make you laugh while it burned. I like to think Bea and Estelle met her with open arms.”

Bea Arthur had passed just a year earlier, in April 2009. Estelle Getty, in 2008. It was as if the universe had been gathering them, one by one, for a reunion off-screen.

Rue’s son held a private ceremony a few days later — small, intimate, with only family and a handful of close friends. There were no cameras, no press, no grand speeches. Just a soft jazz record playing in the background and stories shared between tears and laughter.

At the end, he read a letter Rue had written for him years before:

“Don’t let them remember me for Blanche. Let them remember me for the laughter. Because laughter — that’s how I prayed.”

The Echoes of Golden Light

In the years since her passing, The Golden Girls has only grown in legend. New generations watch it, quoting its lines, celebrating its boldness. But behind every rerun lies the story of four women who carried each other through real life — illness, heartbreak, age, and loss.

Rue once said during a 2006 interview,

“We didn’t just act together. We grew old together. We learned how to say goodbye — one laugh at a time.”

That’s what makes her death feel less like an ending, and more like a curtain call — the last bow in a play that changed how the world saw women, friendship, and aging.

Fans still leave flowers at her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Sometimes, tucked among the roses, there’s a handwritten note that simply says: “Thank you for being a friend.”

What We Never Saw

There’s a story — half rumor, half truth — about Rue’s final morning.

When the hospital staff came in to collect her belongings, they found something curious on her bedside table: an old envelope addressed only with the initials B.A. Inside was a faded photo of Bea Arthur, taken on the set of The Golden Girls, and a single sentence written in Rue’s careful hand:

“Saved you a seat, darling.”

No one knows when she wrote it, or why she kept it close in those last weeks. But for fans who loved them both, that detail feels like fate — as if even in death, Rue was keeping her promise to Bea: “Don’t let them make me smaller.”

The Golden Reunion

If heaven has a studio, you can almost picture it: four chairs, one couch, and a kitchen that never runs out of cheesecake.

Estelle walks in first — tiny, fierce, cracking jokes about St. Olaf. Bea follows, dry and majestic, arms crossed. Betty, radiant as always, brings the laughter. And then Rue — shimmering, barefoot, smiling as if she never left at all.

They sit down, look at each other, and for the first time in years, there’s no pain, no illness, no goodbye left unsaid.

Rue looks around and says,

“Well, girls… we’re all here now.”

And maybe that’s what the nurse saw reflected in the window that night — not ghosts, but the reunion of four souls who made the world laugh and, in the process, taught it how to feel.

The Light That Stayed

More than a decade later, Rue McClanahan’s final night still carries an echo — soft, eternal, unexplainable. Fans speak of feeling warmth when her episodes air, of hearing her voice as if she’s still in the room.

The truth is simpler, perhaps: laughter leaves traces. It lingers in the air long after the sound fades.

When the light dimmed at 1 a.m. that June night, it didn’t go out. It just moved — from her bedside lamp to every screen, every memory, every person she ever made smile.

And so, somewhere beyond the edge of time, Rue McClanahan is still laughing — her voice drifting across the stars, whispering the same words she once said at a charity gala long ago:

“If I make you laugh tonight, then I’m not gone. I’m right here, honey — forever in the punchline.”